Coal is killing Vietnam as wasteful, dirty energy production and lax law enforcement add salt to the country’s gaping environmental wounds

Vedan Vietnam is still a source of controversy almost two years after the Taiwanese MSG-maker agreed to pay compensation to disgruntled farmers whose livelihoods were ruined by toxic waste illegally dumped by the company.

“It’s not over yet. I will continue to appeal against the compensation rate set for me,” Nguyen Lam Son, the only farmer in Dong Nai Province that sued Vedan for damages after local authorities talked others into dropping lawsuits in July 2010, told Vietweek on Monday (March 19).

“The compensation for me is not fair, given the losses I have suffered from Vedan’s discharging activities,” Son said, adding that he had received only one-third of the VND180 million he lost due to the pollution. “Like me, my uncle and a number of farmers in the province have also petitioned [the local government] for better redress.”

In September 2008, government inspectors caught Vedan Vietnam dumping untreated wastewater into the Thi Vai River in the southern province of Dong Nai. The company had escaped detection by hiding pipes underground and in the river, and had been discharging toxic liquids through them for 14 years, massively polluting the surroundings. Facing fierce pressure of a major public boycott, Vedan agreed in August 2010 to compensate affected farmers in Ho Chi Minh City and Dong Nai and Ba Ria-Vung Tau provinces.

While the compensation was considered a rare victory by some, the case also exposed the entrenched lack of enforcement of environmental rules at every level in Vietnam. Experts say the weakness has paved the way for unscrupulous companies to continue destroying the environment.

According to a five-year report released last year by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, water pollution was blamed for an estimated six million cases of illness during the 2006-2010 period. Treatment costs were estimated at around VND400 billion (US$19.5 million), according to the report. The report also recorded a decline in water quality in the nation’s three major river basins: Nhue-Day and Cau in the north and Dong Nai-Saigon in the south.

Experts say that if Vietnam – a densely-populated country smaller than California with more than twice the number of people (the 13th largest population in the world) – forges ahead along its current energy-based growth trajectory, what is left of the country’s precious natural environment could soon be history.

“Surely, Vietnam needs a lot more energy in the future to maintain economic growth and poverty reduction: energy for households and for businesses,” said Koos Neefjes, the policy advisor on climate change for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Vietnam.

“But we have recently researched this and our research shows that Vietnam’s economy is energy inefficient and carbon intensive by comparison with other middle income countries, meaning that it uses a lot of energy and produces comparative large amounts of greenhouse gas per unit of [gross domestic product],” Neefjes told Vietweek.

The Environment Ministry report said Vietnam has spent between 1.5 and 3 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) mitigating environmental pollution that has been rapidly increasing for years. According to the World Bank, those mitigation costs could rise to 5.5 percent of the nation’s total earnings due to worsening pollution.

“Unless the current official plans and policies regarding energy are changed, there will be considerably more pollution from energy compared to the past,” Neefjes said.

“If the government would cease to keep energy prices artificially low and instead use the state revenue for productive, low carbon research and development as well as compensation for poor people, then it would be likely that the increase in energy use and in pollution would be considerably less, and Vietnam would start to move toward a greener future.”

Burning warning

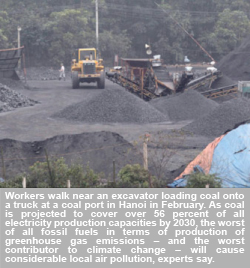

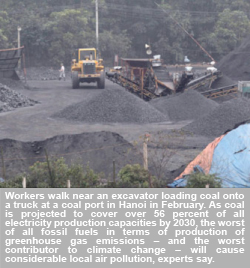

Under a government blueprint, by 2030 coal is projected to cover over 56 percent of all electricity production capacities in Vietnam, making the country an important coal importer.

“That will cause considerable local air pollution as coal is the worst of all fossil fuels in terms of production of greenhouse gas emissions – and it is the worst contributor to climate change,” Neefjes said.

Vietnam is among the top 10 countries with the worst air pollution, according to a study released during this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos. Vietnam"s Air (Effects on Human Health) ranking was 123rd among the 132 countries surveyed.

Vietnam"s environmental performance has been ranked 85th out of 163 countries by another World Bank report released last year, which argues that many natural resources are under threat in the developing nation as strong growth in industrial output has been one of the main factors driving Vietnam"s economy over the past years.

Industrial output in February grew an estimated 22.1 percent from a year earlier, according to the General Statistics Office. In the first two months of this year, mining output, which accounts for around 9 percent of total industrial production value, grew 5 percent. The manufacturing sector, which makes up some 85 percent of total industrial production value, recorded growth of 2.4 percent.

“Environmental costs are frequently not borne by the large polluters such as the mining, construction and manufacturing sectors, which are the sectors that account for most of the growth,” said John Sawdon, a senior environmental economist for the NGO International Center for Environmental Management (ICEM) in Hanoi.

Pollution haven

The Environment Ministry has repeatedly urged both foreign and local companies to go green by “developing sustainable manufacturing.”

But a high-profile pollution scandal involving a major state-owned company last year threw into question the ministry’s “credibility and legitimacy to speak about green business” as it “fails to do its job regulating industry,” said Jake Brunner, the program coordinator for the International Union for Conservation of Nature in Vietnam.

The Dong Nai provincial administration has asked the firm, the Sonadezi Long Thanh Joint-stock Company, to compensate victims for damages incurred by its discharge of untreated toxic waste into a local canal between 2008 and 2011.

The company, chaired by Do Thi Thu Hang, a legislator from Vietnam’s National Assembly (the country’s parliament), had polluted over 16 percent of the 682.8-hectare canal, killing 100 percent of the local aquaculture, and affecting local poultry, investigators said. So far 271 farming households have filed petitions demanding that the company pay a total of nearly VND19 billion ($913,000) in damages.

Experts have pointed to domestic firms, particularly state owned heavy industry, as “some of the most polluting.” And lax enforcement of environmental protection regulations lets them get away with it.

“Both foreign and Vietnamese firms do violate pollution control laws,” Sawdon said.

“They are able to pollute because environmental agencies have insufficient capacity and resources to effectively monitor pollution and enforce… control measures.”

Vietnam introduced its major environment protection laws in 2005 but the lack of government decrees guiding their implementation has puzzled concerned agencies.

“We are still baffled on how to investigate, prosecute and try environment-related criminals,” said Major General Nguyen Xuan Ly, director of the central Department of Environmental Crimes Prevention.

“Many conceptions in the laws have remained vague and too broad to interpret,” Ly said.

Steven Dimitriyadi, president of the Hong Kong-based Quartexx Holdings (which provides outsource services in Vietnam), is looking to move out of the country this June. His company specializes in different domains such as recycled scrap metal, mining or minerals, and finance.

For Dimitriyadi, what is good about doing business in Vietnam is perhaps the no-accountability system.

“You don’t need to be responsible for anything in Vietnam,” Dimitriyadi said, adding it was of course not in reference to his firm.

“Big companies can come in to do what they want to do: pollute [and] walk away. So that’s great about doing business in Vietnam.”

By An Dien, Source: thanhniennews.com

3.jpg)