Conventional wisdom says the economy is weak because consumers, constrained by excessive debt, are cutting back. That is wrong on two counts. I have a chart for each.

As the first chart shows, Americans aren’t cutting back a whole lot. Personal consumption as a share of gross domestic product is floating along at the highest it has been since at least 1948, at 71.1 percent. For comparison, it was way down at 62 percent as recently as the early 1980s.

This inconvenient truth—inconvenient for the “Americans are retrenching” camp, anyway—was pointed out to me by Christopher Thornberg, the founding partner of Los Angeles-based Beacon Economics. He and I were guests on KQED’s Forum radio program on May 4, along with Laura Tyson, the University of California-Berkeley Haas School of Business professor who was President Bill Clinton’s chief economic adviser. Here’s a link to the Forum podcast.

Personal consumption includes spending on imports, by the way, so some of the dollars leak overseas. It also includes almost all health-care spending, about half of which is under the control of the government, as my ex-boss, former BusinessWeek Chief Economist Michael Mandel, always likes to say.

It’s not that consumers are on a shopping spree. It’s that the other sectors are even weaker. Investment is sluggish because businesses are pessimistic about growth; direct government spending (not including transfer payments such as Social Security) is lagging because state and local governments are cutting back; and net exports are negative (i.e., we’re running a trade deficit, albeit one that has shrunk a bit).

Bottom line: As weak as they are, consumers are the engine of this sluggish recovery.

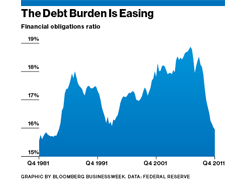

The second chart shows a key reason consumers are not cutting back: They don’t need to. This shows the Federal Reserve’s measure of financial obligations. It’s defined as the ratio of debt payments and other fixed charges to disposable personal income. The fixed charges include car lease payments, rent, homeowners’ insurance, and property tax payments.

Extremely low interest rates are making Americans’ debt sustainable. The burden will increase when rates start to rise, but presumably that won’t happen until the economy is getting stronger and incomes go up.

Says Thornberg: “There’s this ongoing argument that we’re in a painful period of deleveraging. No, we’re not, because there’s no reason at these interest rates for anyone to have to deleverage.”

By Peter Coy - Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

3.jpg)